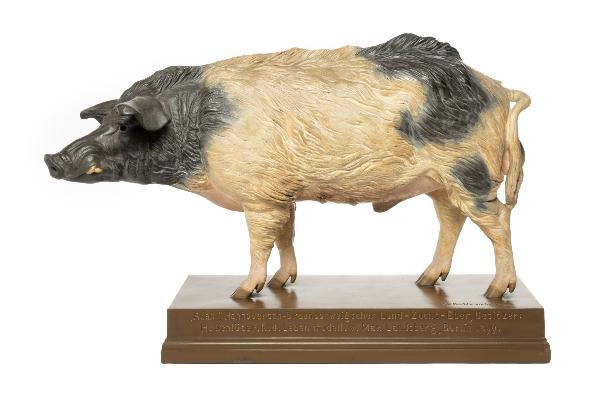

Adam is a Hanover-Brunswick breeding boar, black and white, with a rather primitive appearance. He has of course been dead for decades, and the race of breeding pigs to which he belonged is long since extinct. But cast in plaster, he lives on alongside a host of other pigs, cattle, horses, goats, and smaller animals. Set out neatly in rows, with couples facing each other, the livestock figurines are exhibited in the slightly dusty display cabinets at the veterinary medicine building in Königinstraße. And so Dr. Veronika Goebel is delighted that the collection will be displayed to better effect following the planned move to Oberschleißheim: “Display space is planned for the collection in the new buildings,” says the researcher, who works at the Institute of Paleoanatomy and History of Veterinary Medicine under Professor Joris Peters, current Director General of the Bavarian Natural History Collections (SNSB).

An ear or a tail can break off easily

Overall, the collection comprises 286 domestic animal and livestock specimens – most of which were made out of plaster as teaching models for animal breeding well over a century ago. But there are also some figurines made of porcelain, which were crafted less for the purposes of anatomical presentation than in pursuit of artistic aims.

It is only natural that the specimens have taken a few knocks over the past ten decades. Plaster figurines are delicate and in the process of taking them out of cabinets for use in the lecture hall and returning them again, there has been some attrition. Protruding body parts are especially apt to break off: “It hasn’t been uncommon for a specimen to lose an ear,” says Olaf Herzog.

The sculptor, who works for the Glyptothek museum of ancient sculpture in Munich among other clients, has now repaired the ravages which time had wrought on around 160 figurines. In doing so, he has been very mindful to preserve the original character of the pieces to the greatest possible extent. “I intervened as little as possible,” says Herzog. “The figurines have passed through many hands and have a certain patina that should be preserved.” A major challenge for the restorer is reproducing the color of the statuettes, which were repaired frequently but often amateurishly in the past. “On occasion probably to cover up damage,” suspects Herzog. “They used varnishes that were incompatible with the surface and peeled off,” he explains. And then they might be glued back on, for example. “It’s difficult to reconstruct the varnishes – it requires a lot of time and patience.”

Unique collection

Most of the figurines come from the atelier of the animal sculptor Max Landsberg from Berlin, who made them at the end of the 19th century. They exhibit such anatomical accuracy that you could almost imagine that the animals obligingly stood still while modeling for him. But Olaf Herzog knows from his own experience how hard it is to capture willful beasts in sculptural form. For his masterpiece to complete his apprenticeship as a sculptor, he modeled a bull – an undertaking that led him to the bullrings of Spain to analyze the animals’ movements so that he could translate them into clay. “They are living creatures that move around and do not listen to instructions like life models. It takes days to reproduce movements.” And so it is scarcely any wonder that figurines like the ones in the veterinary medicine collection are so valuable today – not to mention rare. “The collection is unique – there’s nothing like it anywhere else in Germany,” says Veronika Goebel with suitable pride. She is very pleased that the restoration of over 160 figurines was possible thanks to funding by the Department of Veterinary Science.

Herzog documented all the alterations he made. He repaired larger pieces of damage, although sometimes he deliberately left the repairs visible. For weeks he cloistered himself away in Königinstraße, working with original materials and doing a tremendous job – for the figurines, which were photographed before and after, were truly in a sorry state in some cases. Take the Racka sheep, for example, where both of the impressively spiraled horns were broken, or the horn of the Pinzgauer bull, which had been lost over the course of the years.

Although the collection is clearly no longer of any use for the practical training of veterinarians, it documents in a very striking fashion the diversity of animal breeds that once existed, some of which became extinct because of new economic imperatives. “Formerly, pig breeds of the old landraces were often very fat, late-maturing, and slow-growing, but consumers preferred lean meat and breeders wanted fertile and fast-growing pigs,” explains Professor Armin Scholz, manager of the faculty’s teaching and experimenting estate in Oberschleißheim. These changes in consumption habits have resulted in some races no longer being bred and ultimately disappearing. “When breeding objectives are not pursued anymore,” says Scholz, “a breed with traditional characteristics generally cannot be preserved, unless it’s deliberately protected as an important genetic resource.”

Remembering old breeds is another major reason for the restoration of the shorthorn bull, the Racka sheep, and Adam and his female companion.