Ancient poem: “maligned in the basest terms”

1 Apr 2025

Scholars have recently deciphered one of the earliest surviving Greek poems – a piece of invective full of misogyny. Interview with John Weisweiler, Chair of Ancient History at LMU

1 Apr 2025

Scholars have recently deciphered one of the earliest surviving Greek poems – a piece of invective full of misogyny. Interview with John Weisweiler, Chair of Ancient History at LMU

This year’sJohn Buckler Lecture will take place on 28 April. Christian Marek, Professor emeritus of Ancient History at the University of Zurich, will visit LMU to discuss a recently deciphered Greek verse inscription. John Weisweiler, Chair of Ancient History at LMU, explains why the discovery has taken experts by surprise.

Scholars have recently deciphered an inscription from the 6th or early 5th century BC. It was carved into a block of marble and displayed in a public space. What is the text about?

John Weisweiler: The inscription was discovered a few years ago in the ruins of the ancient city of Teos, in what is now western Turkey. It is an extremely obscene poem that heaps opprobrium on a woman called Eunomia, who is maligned in the most vulgar terms.

Here’s a passage to give you a flavor: “When night falls, she often docks in a new harbor / And when she re-emerges, she roams around in a disgusting frenzy / For two nights, soon three, she toils in the bed / Of yet another man.”

Such extreme, misogynist invective is not unusual in Greek poetry. What makes this piece so special, however, is that it is probably one of the oldest surviving examples of Greek verse.

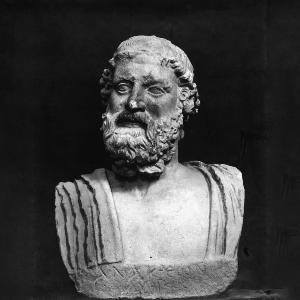

Inschriftlich bezeichnete Marmorbüste des Anakreon. | © picture-alliance / akg-images

Who wrote it?

There are good indications that this poem was composed by one of the very first Greek lyric poets – Anacreon, who continued to inspire poets right up to the German Romantic period. He probably lived and wrote in the 6th century BC and was born in Teos. So it is quite possible we are dealing here with a previously unknown poem from this lyric poet.

The language of the poem sounds shocking to modern ears. Would it have been perceived the same way in antiquity?

I would say that likely depended on the context. Scholars currently believe that many of these poems were performed at symposia – exclusive gatherings of elite men. Would it have been frowned upon in such a setting? Probably not. The truly remarkable thing is that the inscription was displayed in public.

Nearly all known ancient Greek poets were men. However, there is a famous exception – Sappho of Lesbos, who lived in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BC.John Weisweiler , Chair of Ancient History at LMU

Were such poems intended for male audiences at that time?

As a rule, yes. Nearly all known ancient Greek poets were men. However, there is a famous exception – Sappho of Lesbos, who lived in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BC. She wrote poems for young women, whom she trained in the customs of Greek upper-class life. Scholars reckon it was normal among the elites in Greece at that time for girls and boys to spend parts of their youth separated by sex. Young men were brought up in a male community, in which they had to fulfill certain rituals designed to turn them into good citizens. Women, too, appear to have lived in a separate community before marriage—at least in Sappho’s case. Just as her poems were suitable for female society, so the bawdy verse of Anacreon – as well as that of Archilochus, another author who wrote extremely obscene poems in this period – likely belonged to the exclusively male world of the symposium.

We must always bear in mind, however, that apart from these texts, we have no other sources that tell us how these societies worked. When we analyse them, we are caught in a kind of circular reasoning. First, we use these texts to say something about the society in which they were produced. Then, we argue that the way they functioned explains why the texts look the way they do. That being said, the idea that these poems were created in predominantly female or male settings remains a plausible explanation for their existence.

But Anacreon didn’t just write only invective poetry, did he?

No, he is best known for drinking songs and love poetry. But most of the texts that have survived under his name come from the symposium context.

Many of the misogynist tropes that persist today have their origins in the ancient world, where they were invented.John Weisweiler , Chair of Ancient History at LMU

You’ve described these ancient societies as patriarchal. Were they sexist as well?

From a modern perspective, unquestionably so. Many of the misogynist tropes that persist today have their origins in the ancient world, where they were invented. In this way, Greek and Roman texts shape our society to this day. Naturally, misogyny and sexism also exist in other societies, but they use other stereotypes than the ones familiar to us.

In this poem, a woman is insulted by name. Was this common practice?

Yes, it was common in invective poetry to address women by name. However, we don’t know if these were the women’s real names or pseudonyms.

Were men spared such abuse?

Men also wrote scathing invective verse about other men, including about their sexual behavior.

Today, there is an ongoing debate about hate speech and how to regulate it. What was the attitude towards invective poetry in antiquity?

Greek city-states were small communities, with perhaps a few hundred, or at most a few thousand, inhabitants. The elite, who were the main participants in this literary culture, was even smaller. These were people who all knew each other personally. In later periods, there were repeated attempts to crack down on these insults. But as in our time, those engaging in verbal attacks were always a step ahead of their victims. Graffiti found in Pompeii, for example, features crude and often sexually explicit insults.

So hate speech is not a new phenomenon after all, but has deep historical roots?

Absolutely. What fascinates me is that on the one hand, we see the origins of modern social behaviors in antiquity, while on the other, it becomes clear that ancient societies functioned very differently than our own. This, in turn, shows that things do not have to be as they are today. It is striking to observe how certain themes and rhetorical strategies have persisted for millennia, shaping us in both positive and negative ways.

The ancient world also presents us with unexpected elements that force us to develop new interpretations. A case in point is the discovery that this highly offensive poem was on display in a public setting. This shows that this society must indeed have functioned very differently from our own. Today, we would hardly be inclined to publicly exhibit such a coarse piece of invective by one of our classical poets.John Weisweiler , Chair of Ancient History at LMU

Or do we simply project our own perspectives onto the past?

That’s always a risk. However, the ancient world also presents us with unexpected elements that force us to develop new interpretations. A case in point is the discovery that this highly offensive poem was on display in a public setting. This shows that this society must indeed have functioned very differently from our own. Today, we would hardly be inclined to publicly exhibit such a coarse piece of invective by one of our classical poets. In this regard, we may well be more prudish than the ancients– an idea that might come as a surprise.

Very few text fragments from the earliest Greek poets have survived. It was a huge surprise to find a fragment of Greek literature from such an early period inscribed in stone.John Weisweiler, Chair for Roman and Late-Antique History at LMU

A view of the theater | © picture alliance Anadolu Berkan Cetin

Why would a poem like this be carved into a block of marble and placed in a public space?

Very few text fragments from the earliest Greek poets have survived. It was a huge surprise to find a fragment of Greek literature from such an early period inscribed in stone. One possibility is that the city of Teos, centuries after Anacreon's death, sought to preserve and publicly display his complete works in inscriptional form. That would explain why such a provocative poem was committed to stone. But all these remain open questions – maybe Professor Marek’s Buckler Lecture will shed new light on them.

Indeed. Professor Marek will be discussing the poem at LMU on 28 April. What are you most looking forward to in his lecture?

I am delighted that we were able to persuade Christian Marek to deliver this year's Buckler memorial lecture. He is one of the world’s leading experts on inscriptions and played a key role in deciphering the potem. In the lecture, Marek will elucidate the original context in which the text was exhibited – and discuss whether the poem actually can be attributed to Anacreon. His presentation will also provide valuable insights into how hate speech worked in an archaic society.

Professor John Weisweiler holds the Chair for Roman and Late-Antique History at LMU.

Anacreon in stone? An archaic verse inscription from Teos

This year’s John Buckler Memorial Lecture will be delivered by Professor Christian Marek (University of Zurich) on 28 April 2025 at 6:15 p.m. The annual event is organized by the Institute of Ancient History at LMU.

Please register via E-Mail

Interview:

"Poems can change lives"

Portrait:

Hellenistic poetry – a cosmos in six lines