Leaflets in the Second World War: “Ei ssörrender”

16 Sept 2024

From the call to surrender: Students at LMU’s Historical Seminar have designed an exhibition on war propaganda and leaflets during the Second World War.

16 Sept 2024

From the call to surrender: Students at LMU’s Historical Seminar have designed an exhibition on war propaganda and leaflets during the Second World War.

Benedikt Sepp and Roman Schwarz (3rd and 2nd from right) with students from the course. | © LMU

Leaflets were a weapon of war used by all parties in World War II. Millions of them were jettisoned from airplanes, including the last one distributed by the White Rose. At LMU’s Historical Seminar, Dr. Benedikt Sepp formulated the idea for this exhibition with the students on one of his courses. In the interview reproduced below, he and Roman Schwarz – one of the participants who is now in charge of PR for the exhibition – talked to us about how the leaflets affected the course of the war.

The content of the leaflets distributed during World War II was often a mix of truth, propaganda and disinformation. Can they be compared with today’s social media channels?

Benedikt Sepp: In a way, perhaps they can indeed be seen as a precursor of these fake news distributors. Back then, the leaflets were tailored more specifically to their addressees than is the case with today’s fake news. But in both cases, different regimes of truth are set up with a definite purpose. In the case of the leaflets, the purpose was to get soldiers to surrender or even engage in acts of sabotage. Incidentally, this tool is still used by the military to this day.

Roman Schwarz: Although, leaflets didn’t always contain fake news. Some of them were truthful.

We mostly focused on leaflets that were disseminated at the front. Many allegedly sought to correct propaganda. For example, they would claim that there were actually far fewer tanks than the government would have the soldiers believe. Another topic was permits for soldiers, which spelled out how to throw away your weapon and surrender.Benedikt Sepp

Alongside the radio, leaflets were the most important element in psychological warfare. What would we have read on them?

Sepp: That varied. We mostly focused on leaflets that were disseminated at the front. Many allegedly sought to correct propaganda. For example, they would claim that there were actually far fewer tanks than the government would have the soldiers believe. Another topic was permits for soldiers, which spelled out how to throw away your weapon and surrender.

Schwarz: American leaflets intended for German soldiers often depicted what was on the menu for prisoners of war. The Soviet Union added images of soldiers eating and chatting with Russian officers. The Americans even promised offers of further education. These were attempts to paint a positive picture of wartime captivity and encourage the soldiers to give up.

What else would one find on the leaflets?

Sepp: There were elaborate graphics, brutal images of mangled corpses and erotic drawings, but there were often also emotional appeals – saying that the soldiers should finally show responsibility for their families, for example. The marital fidelity of soldiers’ wives was another common theme. When Dresden was bombed, the Royal Air Force even dropped leaflets trying to explain to the local population why the bombing was necessary.

Millions of leaflets were dropped over enemy territory. But were they ever read?

Sepp: Our knowledge of that is limited, because having them in your possession was strictly prohibited. My grandmother experienced several occasions when leaflets were dropped from planes, but she never dared to pick one up. Shortly before D-Day, the Allies used this method to try to educate the Germans about their [the Americans’] dominance. Many people did indeed then surrender. That said, they would probably have done so because the German cities were under siege as well. One study by the US Army from the 1950s found that leaflets intended for children were especially successful. The children didn’t know that it was forbidden to read them, so they often shared the information with their families. Later on, the permits too were often found sewn into the uniforms of German soldiers.

Toward the end of the war, there was less and less content, and the menus for prisoners of war increasingly became the most compelling argument. By this time, leaflets were already being printed at mobile print shops near the front lines.Benedikt Sepp

Did the content and design of the leaflets change in the course of the Second World War?

Sepp: There has been no systematic study of that to date. My impression is that the language used for Soviet propaganda in particular got better and better because of the growing number of prisoners of war. The content, too, improved due to access to inside information. Toward the end of the war, there was less and less content, and the menus for prisoners of war increasingly became the most compelling argument. By this time, leaflets were already being printed at mobile print shops near the front lines. In contrast, the German leaflets got worse and worse – the language especially, probably because many of the translators had died.

Schwarz: When the Italian regime collapsed in 1943, the Allies often used leaflets to assert that Germany would soon suffer the same fate.

Who decided what appeared on the leaflets?

Sepp: It was usually propaganda departments attached to the armies. At the start of the war, everything was still heavily centralized in the Soviet Union. But as time went on, responsibility was gradually passed down the chain of command. On occasion, leaflets would actually be addressed to individual units and would even spread gossip. Much of the content was put together by prominent opposition members who had fled. The Soviets used the words of Communist politician Walter Ulbricht, for example, while the Allies cited people such as Klaus Mann, son of Thomas Mann, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

How did you come up with the idea of organizing an exhibition of leaflets?

Sepp: There have been few serious sources in the past. Klaus Kirchner, on whose private collection the exhibition is based, collected leaflets as a child during World War II. They became his life’s work. He bought them and swapped them and converted his house into a kind of private museum. In terms of its size, his collection was undoubtedly unique – a stroke of luck for the researchers. After his death, the White Rose Institute bought part of his estate.

The exhibition also displays the last leaflet circulated by the White Rose, which was dropped behind German lines by the Royal Air Force. How did it find its way into the hands of the Britons?

Sepp: The Scholls were arrested as they distributed the leaflet at LMU. But it was taken to Britain via Scandinavia by the resistance fighter Helmuth James Graf von Moltke. Millions of copies were then printed and disseminated. The intention was to show the Germans that their solidarity was much more brittle than the National Socialists claimed in their propaganda. A Soviet leaflet picked up the same theme, referring to the members of the White Rose as “heroes” and “examples” for all Germans to follow.

The German army developed a rocket that could distribute leaflets at an altitude of 1000 meters.Benedikt Sepp

If you visit the exhibition, you discover that leaflets were not only thrown out of airplanes.

Sepp: Yes, that is a fascinating subject. There were various techniques that had been tried out way back in history. Some leaflets were simply attached to balloons, for example. And we know that there was also artillery ammunition that contained leaflets instead of explosive materials. The German army went a step further and developed a rocket that could distribute leaflets at an altitude of 1000 meters. To this day, they still have balloons that open a flap to let leaflets drop out.

We had history on the desk in front of us.Benedikt Sepp

The exhibition was developed together with students as part of a course. How did the students react to the course?

Schwarz: We were all very highly motivated. Various lectures were delivered by experts at the start of the semester. I personally was mostly interested in the significance of leaflets from a scientific perspective over the course of time. We are talking about a very old medium. We even visited the archive of the White Rose Institute. I was especially fascinated by leaflets that were still rolled up, that didn’t open up when they were ejected.

Sepp: Students of history seldom get to hold something really old in their hand. Klaus Kirchner’s estate was not packed up in neat archive boxes. Some of it was moldy, partially burnt or crumbling. So, we had history on the desk in front of us. It was no surprise, then, that the course was fully booked in short order. The participants were very keen and really worked hard to make the exhibition happen.

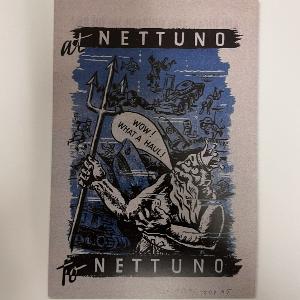

Some leaflets even took recourse to deities and the ancient world.

Which leaflets stay most vividly in your mind?

Schwarz: An Italian leaflet portraying the Neptune, the Roman god of the seas. As tanks and corpses sank in the background, he was saying English words to the effect of: “What a tremendous haul!” As a student of Latin, I was fascinated to see how recourse was made to deities and the ancient world.

Sepp: There are two that stick in my mind especially. One is a simple document bearing the words “Ei ssörrender” (“I surrender” with a German accent). Because of the language barrier, many soldiers didn’t know how to surrender, so this one shows that the leaflets were read on the battlefield and not at a desk, and what their specific purpose was. The other is a leaflet addressed to a particular division in Swabia, South Germany. An appeal was made to the “Pride of the Swabians” – which shows leaflets were at times addressed to very small niche groups.

"A bomb full of flyers. Exhibition about propaganda leaflets from the Second World War"

Extended until October 15 2024

Lobby of the Historicum Library, Schellingstraße 12, 80799 München