Lost books, stolen home

5 Feb 2024

The private libraries of German-Jewish collectors were plundered during the Nazi period. Historian Julia Schneidawind investigates their fate.

5 Feb 2024

The private libraries of German-Jewish collectors were plundered during the Nazi period. Historian Julia Schneidawind investigates their fate.

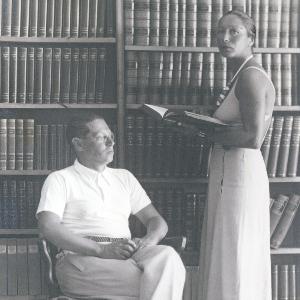

Edith Rosenzweig and her son Rafael. | © Lotte Fürth (1925)

Keeping thousands of books at home requires a lot of domestic infrastructure. But for all their imposing physicality, bookcases are really intellectual furniture and represent cultural self-assurance. Indeed, they are a “world beyond the world” in Stefan Zweig’s phrase and constitute a spiritual home and estate for their owners.

All this helps to explain why German-Jewish scholars and writers and their families took such pains to save private book collections from the clutches of the Nazis.

A prime example is Edith Rosenzweig, widow of the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929). Six years after her husband’s premature death, Edith devoted a room in her new apartment in Frankfurt to the 3,000 or so books he had left behind. The couple saw the books as a legacy for their only son, through which he would discover what kind of person his father was.

Alas, it was not to be. In the wake of the Night of Broken Glass in 1938 and the massive spike in the persecution of Jews, Edith Rosenzweig first sent her son to Palestine and then began dissolving her household in Germany and arranging for the collection to be shipped to the Levant. Family and books went into exile.

Following various delays and complications, a ship carrying the books finally departed Hamburg via Antwerp in 1940 just before the German army occupied Belgium.

However, the ship was seized off the coast of Tunisia by officers of the French protectorate and diverted to Tunis. To this day, the Rosenzweig collection is part of the library in the Tunisian capital. Rosenzweig’s son never got the books.

Julia Schneidawind sees little prospect at this stage of the books and manuscripts finding their way to Israel. But there is one silver lining, observes the historian at the Chair of Jewish History at LMU, in that the collection is almost wholly intact. Unfortunately, however, political and religious tensions make it difficult for Israeli researchers to visit the library.

“I hope to launch a project to make the collection in Tunis available to researchers at least in digital form,” says Schneidawind, who herself did research in Tunis for her dissertation.

In her book “Schicksale und ihre Bücher. Deutsch-jüdische Privatbibliotheken zwischen Jerusalem, Tunis und Los Angeles” [which translates as: “Fates and their books. German-Jewish private libraries between Jerusalem, Tunis, and Los Angeles”], she looks at the fates of the private libraries of the writers Lion Feuchtwanger, Stefan Zweig, Karl Wolfskehl, and Jakob Wassermann in addition to Franz Rosenzweig’s.

In undertaking this project, she sought not only to trace the fates of the books, manuscripts, autographs, incunables, and so forth, but also – and more importantly – to show what the loss meant to the individual scholars and how they dealt with it.

“After all, the libraries weren’t just a collection of books. They were family archives spanning generations – and also an archive of friendships and networks. Moreover, they were resources for the intellectual work of their owners,” says Schneidawind.

Lion and Martha Feuchtwanger in their library in Sanary-sur-Mer in the south of France, 1935 | © USC Digital Library

Lion Feuchtwanger had to rebuild his library twice. The first time was during his exile in Sanary-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, after his villa in Berlin, including his book collection, had been ransacked by Brownshirts in 1933.

With the collection in the south of France soon numbering some 2,000 volumes, Feuchtwanger was able to resume something akin to his normal working life. When the German army invaded Poland, however, the writer and his wife were classified as “enemy aliens” under a policy that provided for the internment of all Germans under the age of 65 resident in France. The Feuchtwangers were duly interned, and the collection in their house by the sea was lost once again.

In the United States, where the couple was finally able to emigrate, they built up a large library again – in Pacific Palisades at the gates of Los Angeles. The collection is held today in the Lion Feuchtwanger Memorial Library at the University of Southern California.

The acute risk faced by private German-Jewish collections during the Nazi period sets them apart from similar collections of non-Jewish origin, says Julia Schneidawind. This is also the reason, she notes, why so few Jewish libraries have survived intact. They were plundered, destroyed, or scattered to the four corners of the Earth.

An exception to this rule is the library of Jakob Wassermann. Schneidawind explains: “The collection was taken over by a non-Jewish neighbor, whose family members gradually added literature that followed the party line. This resulted in works of Nazi ideology sharing shelves with traditional Jewish works. Nevertheless, the Wassermann library is preserved today in Nuremberg.”

Lion Feuchtwanger largely recovered from the shock of losing his books and being forced into exile. Meanwhile, Karl Wolfskehl sold his collection to the German-Jewish businessman and bibliophile Salman Schocken, which enabled him to go into exile in New Zealand to escape the Nazi terror.

Things panned out differently for the Austrian writer and journalist Stefan Zweig, a serious bibliophile whose huge collection contained precious autographs among other valuable works.

His first wife Friederike described the book situation in Zweig’s apartment as follows: “In a long, narrow room […] the shelves reached to the ceiling.” Moreover, the author used his kitchen mainly for cataloguing to structure and document his collection.

This made Zweig’s flight from the Nazi regime – first to England, and subsequently to Brazil when he feared the German army would invade Britain – all the harder to bear, as he lost his collection along the way.

After all, the libraries weren’t just a collection of books. They were family archives spanning generations – and also an archive of friendships and networks. Moreover, they were resources for the intellectual work of their ownersDr. Julia Schneidawind

“When the Nazi period began and I moved out of my house, my pleasure in collecting vanished, as did any confidence that anything would remain of my collection. For a while, I kept parts of the collection in safes and at friends’ houses, but then, remembering Goethe’s admonition that museums, collections, and armories that cease developing are wont to ossify, I decided that, since I could no longer devote my own efforts to forming and shaping my collection, I would take leave of it instead.” (Stefan Zweig)

“For Zweig, it was a catastrophe to lose his home country and his collection,” says Julia Schneidawind. “How was he meant to work without his library? Access to public libraries was just not the same for him.” She continues: “The various authors dealt with the loss in very different ways. Some carried on regardless, while for others it was as if their whole world had collapsed.”

In 1942, Stefan Zweig and his wife Lotte took their own lives in the Brazilian city of Petropolis, having taken an overdose of sleeping pills.

The aforementioned businessman Salman Schocken not only helped with the expedition of individual collections, but also purchased whole collections and organized their transportation to Jerusalem – including the collection of Karl Wolfskehl.

“Schocken knew it contained some very valuable and interesting pieces,” recounts Julia Schneidawind. “But he also bought them in the knowledge that it would help Wolfskehl, who was in enormous difficulties.” However, says the historian, he did not buy everything, which was no doubt partly a matter of funds.

Although Wolfskehl’s collection made it to Jerusalem, where it remains to this day, it is not complete. “Schocken’s heirs sold off German literature, for instance, because they took the view that such works weren’t needed in Israel anymore.”

As such, Schneidawind suspects that even if Franz Rosenzweig’s library had reached its intended destination, it would not have been preserved almost intact as it is today.

Stefan and Charlotte Zweig at work together, Petrópolis (Brazil) 1941. | © akg-images

Edith Rosenzweig also solicited Salman Schocken’s aid to ship her deceased husband’s library. The businessman was happy to help, drawing on his extensive contacts. Edith did her utmost to rescue the books and fulfill her husband’s dying wish that the collection would one day belong to their son.

“Women play a key role in the story of private libraries,” explains Julia Schneidawind, who wanted to give due consideration to this aspect in her work. She points out that these were also family libraries and contained the books of wives, mothers, and grandmothers.

Martha Feuchtwanger, for example, contributed a lot to the collection of her husband, while his secretary Lola Sernau tried – successfully in the end – to salvage part of his library and send it after him. And finally, Charlotte Zweig shared her husband’s fate and died at his side. Women played an important role and even bore the main responsibility for saving the books, even if they did so mostly from the shadows. The sentence with which Edith Rosenzweig ended a letter to an acquaintance from her Frankfurt days is most apposite in this regard:

“Things will work out somehow and I’m not so important as to get all worked up or frightened. What does bother me is the increasing loneliness.”

Julia Schneidawind

Schicksale und ihre Bücher. Deutsch-jüdische Privatbibliotheken zwischen Jerusalem, Tunis und Los Angeles

Volume 34 of series Jüdische Religion, Geschichte, Kultur

Edited by Michael Brenner and Stefan Rohrbacher

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 2023