Quantum physics: Encryption in space

24 Mar 2025

Bona-fide pioneering: a team of LMU quantum physicists is using a nanosatellite to test new technology for hack-proof quantum cryptography. Read about the early days of a trailblazing mission.

24 Mar 2025

Bona-fide pioneering: a team of LMU quantum physicists is using a nanosatellite to test new technology for hack-proof quantum cryptography. Read about the early days of a trailblazing mission.

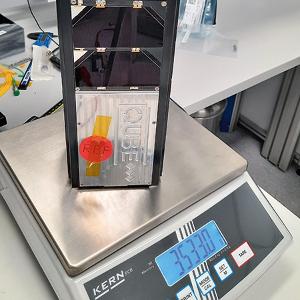

It is Friday evening, 16 August 2024. In the testing hall at the Center for Telematics (ZfT) in Würzburg, the mood swings between euphoria and nervous tension. The cause of these emotions is a shoebox-sized nanosatellite weighing around three-and-a-half kilograms, which is finally embarking on its journey into space. Years of elaborate, painstaking work have gone into its construction, and it has been fitted out with all manner of high-tech gadgetry. It will need nothing less. Its ambitious mission is to test newly developed components for hack-proof communication through quantum encryption from space. Before it can do that, however, the launch of the SpaceX rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California must be successful. It has been postponed several times, but on this day the conditions are nigh-on perfect.

Read more about the topic heritage in the current issue of our LMU magazine EINSICHTEN at www.lmu.de/einsichten.

The idea of exploiting the laws of quantum mechanics to encrypt information originated in the 1980s. Essentially, it involves using quantum mechanical properties, such as the polarization of photons – in simple terms, their direction of oscillation – or the excitation of atoms. “An eavesdropper who attempts to acquire information through any type of measurement would be discovered, because this very action would alter the state of the quantum system,” explains Harald Weinfurter, Professor of Experimental Quantum Physics at LMU, member of the MCQST Cluster of Excellence, and pioneer of quantum cryptography.

Thus, this method of hack-proofing is based on fundamental laws of physics. With conventional cryptographic methods, this is not the case. Quantum computers are capable in principle of cracking classical keys, such as those generated for most online processes. Consequently, if this technology actually becomes viable, the majority of today’s encryption methods will no longer be secure. Clearly, we need to do something about this.

The only critical moment is the launch, when there are the most vibrations. Once up in space, it’s actually pretty quiet.Harald Weinfurter

Weinfurter and his staff at LMU have been investigating the possibilities and limits of quantum cryptography for over a decade. The team celebrated a breakthrough in 2022 when it demonstrated that a key can be exchanged using two entangled quantum systems consisting of two rubidium atoms. Located in laboratories 400 meters apart on the LMU campus, the two systems were connected via a fiber optic cable 700 meters in length, which ran beneath Geschwister Scholl Square in front of the main university building.

Unfortunately, however, attenuation is a major limitation of fiber optics: “Every 50 kilometers, the signal strength decreases by a factor of ten – so after 50 kilometers, we’re left with only ten percent of the signal; and after 100 kilometers, there’s one percent left; and so on,” says Weinfurter. That is why commercial systems – and yes, there are some already on the market – are typically designed for a distance of around 70 to 100 kilometers. But might it be possible to do more?

Sending light over free-space could work across much greater distances. Yet, it is not always feasible because one needs a clear line of sight between sender and receiver. As part of a European collaboration, Weinfurter’s group pulled off a spectacular quantum key exchange using this method in 2007, over a distance of 144 kilometers between Tenerife and La Palma. To do this, they sent the photons over the cloud ceiling where the air was dry. Unfortunately, such conditions do not prevail often.

But what if one of these locations was in space? From there, the photons would generally have a clear path to a receiving station on Earth as already shown using the large, Chinese satellite MICIUS. This is where QUBE comes into play, an interdisciplinary consortium initiated by Weinfurter and funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). In addition to the Center for Telematics and LMU, other members include the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light in Erlangen and the German Aerospace Center (DLR). Through QUBE and the successor project QUBE II, which is already underway, the participants want to demonstrate that quantum keys can be exchanged between a small, economic satellite and the Earth.

To answer this question, the Center for Telematics team in Würzburg developed the basic structure of QUBE. And the Munich team designed and contributed a complex quantum module – high-tech packed into the tightest of spaces: “It’s a small circuit board with four lasers on it, which can generate photons in four specific quantum states,” reports Weinfurter.

The satellite also contains a miniature optical telescope contributed by DLR. Inside of this telescope, there is a tiny, finely adjustable mirror which is able to direct the photons precisely to the DLR ground station in Oberpfaffenhofen, where staff will try to capture the photons with a mirror telescope and determine their polarization.

Having explained that the tiny mirror is one of the most sensitive components in the satellite, Weinfurter adds reassuringly: “The only critical moment is the launch, when there are the most vibrations. Once up in space, it’s actually pretty quiet.” That being said, there are other dangers out there, such as high-energy radiation from the depths of space which could destroy the electronics. “This could cause a memory chip, say, or a transistor to break,” says Weinfurter, noting that space travel always faces this threat. And naturally, sufficient precautions have been taken to protect against such risks. If the experiments work as planned, quantum satellites like this could be used in the future to create global networks for hack-proof communication.

You could securely communicate between pretty much any two places on Earth so long as you trust the satellite.Harald Weinfurter

Weighing in at 3,533 kilograms. | © ZfT

But first, QUBE has to be carried successfully into Earth orbit. So back to the launch party in Würzburg: In the hall, everybody is transfixed as they follow the fate of the small satellite on the livestream. At 20:56 Central European Time, the moment arrives. The rocket lifts off with a mighty din. After two hours, QUBE is released at an altitude of around 500 kilometers. There are relieved faces when radio contact to the quantum satellite is established. But everybody knows: There is still a long way to go to complete the mission.

Over the coming weeks, the research team in Würzburg will be testing communication with the ground station. This includes things like executing certain commands: “Save data, install updates, check batteries,” enumerates Weinfurter. “It’s kind of like booting up a computer – except that you can activate the on-board computer for just a few minutes per day,” explains the physicist. This is because the satellite is orbiting the Earth and can establish radio contact with the communication center for only a brief time window every day. “For our experiments, we’ve got five minutes max.” But we are getting ahead of ourselves. The expert dampens the euphoria by noting: “Our components will start running only when everything else is operational.”

A few days after the launch, the first delays arise: Only 30 percent of the data packets, which the satellite sends via microwaves, are received. The good news: “The satellite’s antennas must have deployed; otherwise we wouldn’t have got any signal,” says Weinfurter. So the Würzburg team is looking for the problem on Earth, testing the orientation of their receiver antennas and the signal amplifiers, adjusting settings. By mid-October, communication has been established with the satellite. Further tests follow, among them the precise orientation of QUBE in space, which is a prerequisite for the subsequent quantum experiments. To this end, the satellite uses a miniature camera, which photographs the stars and compares the images against a database in order to determine its position.

Weinfurter and his team plan to test their module during the winter months: “We’ll check, for example, whether all components can be activated and switched on.” He is optimistic that the first quantum experiments can begin in spring 2025. Presumably, the weather will be more reliable then. This matters because when skies are cloudy, the light does not get through to the ground.

And even when there is a clear line of sight, the photons will spread over a circular area 150 meters in diameter, notes Weinfurter, because the current optics do not permit more precise targeting. “We’ll start with around 50 photons per pulse; maybe it’ll even work with just 10.” Even at these rates, a photon will land in the telescope only occasionally. “When that happens, the first step is to measure the polarization of the captured photons,” says Weinfurter.

In a second step, the team will try to use such detections for the quantum mechanical key exchange. Here, both the sending and the measuring of the polarization states must occur in the same basis, as the physicists put it. The sender, generally called Alice, randomly selects one of two bases for each photon she sends. Bob, the receiver, also measures in one of the two bases. The bases selected by Alice in each case are communicated to Bob after the fact. Only the photons measured in the same basis contain information about the key.

The bases can even be exchanged publicly, because this subsequent information no longer helps any eavesdropper – or “Eve” as the convention has it. Eve would have to use her measurements for both base settings, causing an error in transmission. This in turn would alert Alice and Bob to the presence of an eavesdropper. Based on the error rate, the two could even determine the proportion of information that has been intercepted.

The next step would be to build up a network of entangled quantum systems on Earth.Harald Weinfurter

If everything goes according to plan, the mission will demonstrate that the components are suitable for exchanging a quantum key. In the successor mission, QUBE II, which is headed by Weinfurter’s colleague Lukas Knips, the planned nanosatellite will be twice as large. Already under construction, QUBE II will have better optics that will enable more precise targeting. Then it should be possible to send and detect individual photons. “There was never any doubt that the exchange of keys would only really become possible with the successor mission.” For this purpose, Knips is developing new equipment for the satellite, including an additional processor board to control the key exchange.

So let us assume that it will become possible to send quantum keys through space. What would such communication look like in practice? “A satellite could exchange a key with Oberpfaffenhofen, for instance. Then it continues its orbit and exchanges a key with some other location on Earth,” explains Weinfurter. “In this way, you could securely communicate between pretty much any two places on Earth so long as you trust the satellite.” This system, therefore, is just about sharing the key – the encrypted data is still exchanged via existing infrastructure and then decrypted on the respective terminals.

“A further step would be to build up a network of entangled quantum systems on Earth,” says Weinfurter – similar to the aforementioned experiments with rubidium atoms. “Such connections would be truly secure, because there is no information present at intermediate nodes to be intercepted, also enlarging the reach of fiber based systems.” And if quite a number of challenges remain to be mastered before this can become a reality, there is no need to be discouraged – pioneering was never meant to be easy.

Prof. Dr. Harald Weinfurter is Professor of Experimental Quantum Physics at LMU. Born in 1960, Weinfurter studied Technical Physics at TU Wien, where he completed his doctorate. He worked as a research associate at the Hahn Meitner Institute in Berlin and at the University of Innsbruck. Having obtained his habilitation degree at the latter institution, he came to LMU in 1999. Weinfurter is a member of the MCQST (Munich Center for Quantum Science and Technology) Cluster of Excellence.

Read more articles from "EINSICHTEN. Das Forschungsmagazin" in the online section and never miss an issue by activating the magazine alert.