The first dropout

16 Jan 2023

Living in and with the wilderness: Literary scholar Klaus Benesch on the brilliant author and philosopher Henry David Thoreau and his influence on today’s world-weary generation

16 Jan 2023

Living in and with the wilderness: Literary scholar Klaus Benesch on the brilliant author and philosopher Henry David Thoreau and his influence on today’s world-weary generation

On 12 September 1920, the New York Times published an article on the fascinating yet difficult personality of Henry Thoreau. The writer, who had passed away half a century earlier, is decribed as a brilliant, solitary figure to whom his contemporaries responded with both wonder and admiration. Thoreau, according to the Times, was an eccentric oddball and extremist whose way of life and whose writings were provocative, especially the autobiographical Walden; or Life in the Woods which relates the two years he spent as a recluse at Walden Pond, shunning society.

On 4 July 1845, American Independence Day, Henry David Thoreau, who was born in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1817 and died there in 1862, moved into a wooden cabin at Walden Pond, just about 1½ miles from the house of his birth. He had built the house himself, on a piece of land owned by the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson. Living alone in the ten-by-fifteen-foot cabin in the woods, Thoreau tried to be self-sufficient as possible. Sporadically, he would venture into Concord to buy, among other things, “two second-hand windows with glass” for $2.43 and “one thousand old bricks” for four dollars, as he meticulously noted. According to his accounts, the whole house cost him $28.12, including transportation: “I carried a good part on my back.”

Thoreau and his uncompromising way of life remain to this day an inspiration and a role model for all those who believe in the power of individual rebellion, spiritual self-reliance, and the importance of an alertness vis-à-vis the environment.Prof. Klaus Benesch

Read the answers in the new issue of our research magazine EINSICHTEN at www.lmu.de/einsichten. | © LMU

The son of a pencil maker, a Harvard graduate, and a former schoolmaster, Thoreau was well known as a writer, philosopher, and speaker during his lifetime. Klaus Benesch, Professor of English and American Studies at LMU and currently “LMU International Research Professor” at Harvard University, who published widely on Thoreau’s works, describes him as an icon of American popular culture comparable to American idols such as Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Elvis Presley. Contrary to the latter, however, Thoreau attained popularity primarily through a place: Walden Pond. A place that has since become a kind of Woodstock for his modern and postmodern followers. Today, Walden represents an “adventure on the doorstep,” as WALDEN, a German lifestyle magazine named after Thoreau’s refuge, calls it.

“Thoreau and his uncompromising way of life,” Benesch contends, “remain to this day an inspiration and a role model for all those who believe in the power of individual rebellion, spiritual self-reliance, and the importance of an alertness vis-à-vis the environment.” In numerous critical essays, Benesch has paid tribute to Thoreau and his place-bound way of life, with regard to Thoreau’s placial iconicity (Where I Have Lived, and What I Lived For?), in the context of the modern politics of place (Cultural Immobility), the confrontation between nature and culture (Day and Night), the influence on American architecture (How I Built This), or his emphasis on walking as a way of thinking (Modern(s) Walking). The literary scholar also describes the various text genres Thoreau employed: essays, speeches, travelogues, philosophical treatises, an autobiography, countless pages of correspondence, and more than 7,000 pages of diary entries.

Thoreau, whom a journalist once called the “father of all rebels,” had not been showered with praise by his contemporaries. An astute observer and critic of his times, he exposed the entanglement of the Northern economy with the slave-owning of the Southern states, rebuking the North for making a profit from the plantations of the South. True, as a “sublime poet of escape and mystery” (SZ) he celebrated the beauty of the natural landscape or delighted in the reflection of the sun in the still waters of Walden Pond and swaying of blossoms in the wind. But Thoreau was first and foremost concerned with his humanity, with what he called the “good life,” a life that is sustainable and in unison with natural world.

Benesch quotes from Walden. “I went to the woods,” Thoreau writes, “because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life.”

His resounding criticism of his contemporaries for living “wrongly” made Thoreau an object of suspicion during his lifetime. Nineteenth-century Americans considered themselves pioneers and builders of a nation in a “New World,” breathing, as one commentator put it, the “fresh morning air of the new continent.” Hence Thoreau’s criticism and rejection of modern civilization seemed pretentious.

Anything that transcends the natural cycles of giving and receiving and does not put man equal to nature is entirely rejected by Thoreau.Klaus Benesch

He was certainly not squeamish. In the first chapter of Walden, Thoreau openly mocks the “conditio americana,” a criticism that can hardly be taken as anything but a taunt. “Men labor under a mistake. By a seeming fate, commonly called necessity, they are employed, as it says in an old book, laying up treasures which moth and rust will corrupt and thieves break through and steal. It is a fool’s life, as they will find when they get to the end of it, if not before.”

Thoreau, on the hand, appeared to have been a “man of leisure” as the New York Times calls him in the title of the above-quoted article. The Times also mentions how he had spent a night in jail because he had refused to pay his taxes. Ralph Waldo Emerson, his friend and patron, after paying his debt and having him released from jail, had asked Thoreau, “Henry, why are you here?” Whereupon he instantly replied, “Waldo, why are you not here?” This “Yankee” reply, wrote the Times, was “rather ungrateful,” given that it was Emerson who supported Thoreau and enabled his rebellious way of life.

Small wonder that the Times, like many of Thoreau’s contemporaries, had been rather critical of Thoreau. As “essentially a man of leisure [who] did no more work than was necessary for his purposes,” it dismissed this eminent thinker as a kind of “a loafer” and even “an aristocrat.”

Yet Thoreau’s rebelliousness notwithstanding, “to most of us,” the Times conceded, “who must tug the collar and tread the mill, living largely according to other people’s standards and working rather for the accidents and decorations than the essentials of fortunate life, his economic and social independence is an object of envy.” Rather than succumbing to the economic realities of capitalism, Thoreau was a man who really “thought for himself and expressed his own opinion in his own way.”

Thoreau achieved his fame, which persists to this day, through his writings. One of the most frequently cited English-language authors, The Quotations Page ranks him at 10th position, after Gandhi and Nietzsche, and before Emerson. His subject matter, a righteous life in an unspoiled nature, clearly appeals to the Zeitgeist of the present day. His ideas can be situated somewhere between Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s late-18th-century critique of civilized existence in a corrupt society and the modern self-made movement and its “Whole Earth Catalog.” Today Thoreau today is a kind of post-heroic Robinson Crusoe in the maker space. As he writes in Walden, having a little world all to himself, he could have been “the first or last man.”

Thoreau’s works are often subsumed under a mode of writing that has recently drawn a lot of attention: nature writing. A broad literary umbrella, according to Klaus Benesch, that encompasses ecology texts and nature poetry, natural history and natural philosophy, publications by environmental movements, guides to living off-grid and living sustainably, naturalism as well as nature mysticism. The scientific analysis of ecosystems, a pure contempt for civilization, esoteric understanding of trees, the neoconservative yearning for the real, in short, a supposed return to the authenticity of untouched nature, are all bedfellows here.

A world of yearning: as can be gleaned from the poetic works of 2020 Nobel Prize laureate Louise Glück, in nature writing the intensive experience of nature, the profound experience of times of the day and the seasons, of plants, weather, light, and night are key to true existential experiences. Mindful observation of nature and slow introspection are synonymous here, often associated with a turning away from the destructive forces of culture and a capitalism that is running at full speed and appears to be out of control.

In contrast to that stand the myth of a nature that is true to itself and the assertion of resilience. This ostensible holism is strongly reminiscent of what Romanticism called “universal poetry,” the “sleeping song in things abounding” (Eichendorff). Even if many his ideas can be connected to these notions, they do not do fully justice to Thoreau’s thinking.

Thoreau wondered what is the original of human nature and what the facsimile, the overpowering of human nature by commerce and capitalism.Klaus Benesch

Benesch calls Thoreau a “non-conquering puritan,” someone who did not want to subjugate nature by taking it as a mirror for his own yearnings and reading into it what he himself felt. Thoreau was no romantic. His retreat to the woods was above all an attempt to rid himself of what he perceived as the burden and onslaught of modernity, for which the whistle blowing of passing locomotives at Walden Pond become an unmistakable symbol.

His rebelliousness and counter-cultural life style was thus determined primarily by the question of how to live as a philosopher in harmony with his philosophy. “To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts,” writes Thoreau in Walden, “but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust. It is to solve some of the problems of life, not only theoretically, but practically.”

Thoreau sought to prove that man can bridge the existential gap between intellectual needs and material necessities and succeed in (and in spite of) modernity by reconciling the antithesis of culture and nature, man and being. His was an attempt to get back to the foundations of man, that which allows him to live in the world and not against it. “The artificiality of modern life,” Benesch argues, “Thoreau is too high a price to pay for the exploitation of all natural resources.” He quotes from Walden: “I let [the land] lie, fallow, perchance, for a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

As Benesch points out, “Thoreau wondered how one can still, in modernity, distinguish between the superficial and and the inner core, between the genuine in human nature and the facsimile, in other words, the overpowering of human nature by commerce and capitalism.” Thoreau’s response to these challenges is, “an uncompromising, almost monkish attitude towards any kind of material desire. Anything that transcends the natural cycles of giving and receiving and thereby alienates man from nature Thoreau entirely rejects.” Rather than experiencing or ‘feeling’ nature, Thoreau wanted to reconcile himself, to find his own inner self.

How then, if at all, are we to define Henry David Thoreau? Perhaps we should call him a metaphysical naturalist, one who wishes to defend man against the onslaught of modernity. This at least seems a more appropriate characterization than the fashionable “nature writer,” a label that evokes an understanding of nature of which Thoreau himself was highly suspicious.

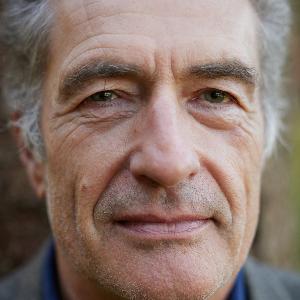

Klaus Benesch | © Oliver Jung / LMU

Prof. Dr. Klaus Benesch is Chair of North American Literature at LMU since 2007. Born in 1958, Benesch received his doctoral degree from LMU and earned his Habilitation at the University of Freiburg. He was Director of the Bavarian American Academy (Munich) from 2006 to 2013 and a visiting professor at the University of Massachusetts (Amherst), Weber State University (Utah), Stanford University, École normale supérieure (Lyon), Université de Bordeaux (Montaigne), Venice International University (San Servolo), and the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland). He has been a member of various DFG-funded collaborative research initiatives and research groups, such as the Collaborative Research Center (CRC) “Cultures of Vigilance.” He recently published a book titled Mythos Lesen. Buchkultur und Geisteswissenschaften im Informationszeitalter (The Myth of Reading. Book Culture and the Humanities in the Information Age, 2021). Benesch is currently “LMU International Research Professor” at Harvard University, in Cambridge, MA.

Read more articles of the current issue and other selected stories in the online section and activate our free magazine alert.