What became of them? Children of the Jewish School in Munich

21 May 2024

Researchers and students at LMU have traced the fates of children from the Jewish Public Elementary School in Munich. The research was inspired by a class photo from 1937.

21 May 2024

Researchers and students at LMU have traced the fates of children from the Jewish Public Elementary School in Munich. The research was inspired by a class photo from 1937.

Where is he now? And what’s she doing, I wonder? When’s the next class reunion?

Questions like these are common when we look at class photos. This genre of photography carries a powerful emotional charge, because it awakens memories, reinforces our identity, but also makes us realize our lack of knowledge about people who were once so familiar: We hope things will have turned out all right for her and for him …

In the case of the class photo from the estate of former Orientalist and LMU professor Karl Süßheim, we now know: 11 of the 47 classmates of his daughter Margot, with whom she went to school on Herzog Rudolf Street and who look into the camera with smiles or curious or expectant expressions on their faces, did not get to live their lives. They and their teacher Ferdinand Kissinger – great-uncle of subsequent US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger – were murdered by the National Socialists.

The other pupils managed to flee from the Nazi terror before it was unleashed in all its brutality after the Night of Broken Glass in 1938. They established new lives in various parts of the world, becoming lawyers, scientists, artists, ambassadors, and writers. Karl Süßheim fled with his family to Turkey, where he died in 1947.

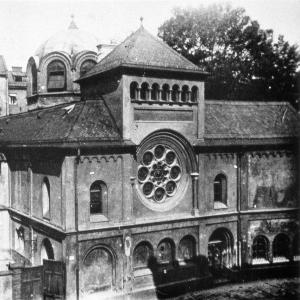

The Public Elementary School is attached to the right of the sacred building. The building complex was destroyed in the Night of Broken Glass in 1938. | © Stadtarchiv München

“I found the class photo while researching my dissertation about Karl Süßheim in the United States. It was part of his estate, which his granddaughter looks after,” recounts Dr. Kristina Milz from the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History in Munich, who also researches at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. She immediately recognized the huge potential of the photo as historical source material, which was confirmed by the supervisor of her dissertation and director of the Leibniz institute, Professor Andreas Wirsching.

Together with her colleague Dr. Julia Schneidawind from the Chair of Jewish History and Culture at LMU, she initiated a project to research the fates of the children and thus, among other things, close a public commemoration gap in Munich.

“Researching 48 biographies is a tall order for two people,” observes Milz. And so the two historians offered a project course at LMU during the 2023/24 winter semester, which had an active research component alongside the imparting of source study skills: 13 students set out to look for sources on the lives of the children.

While Julia Schneidawind taught the main foundations of Jewish history in the 19th and 20th centuries, Kristina Milz, who writes for various media outlets alongside her historiographical investigations, provided important insights into biographical research and the composition of texts. The historians wanted to demonstrate how historical research into a single photo with little information can reach out and touch general history and where the opportunities, challenges, and limits of this approach lie.

“We didn’t exactly know before the project course what sources we would find about which children. We just had a rough idea,” says Julia Schneidawind. The historians deliberately assigned challenging biographies to the participants alongside ones they anticipated would be easier to research. “We wanted to ensure that all students worked on at least one fate where they could make good progress and one where sources would be difficult to find.” Learning that sometimes you just hit a brick wall is an important lesson, notes Kristina Milz.

Mavie Schlehe, a fourth semester student of history and German for academic high school teaching, liked this approach: “In the project course, we really got to experience how historical research works: Sometimes you’re lucky and get loads of source material and almost don’t know where to begin. And sometimes there’s just nothing.”

We didn’t exactly know before the project course what sources we would find about which children. We just had a rough idea.Dr. Julia Schneidawind

Student Mavie Schlehe has been investigating the fate of Edward Engelberg (No. 35). | © privat

First, the students had to decipher the names of the children that Karl Süßheim had noted in German cursive script on the back of the photos. “That wasn’t easy at all, but it was a great exercise because it thrust us right into the research process,” says Schlehe.

Süßheim’s meticulous nature aided their work: There were the names. The next step was online searches – using search engines and family databases. “This uncovered quite a lot of information.”

About Eduard Engelberg, for instance – later Edward – who is numbered 35 on the class photo. His family managed to escape to the United States via Switzerland. “His father was imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp for a while,” recounts Mavie Schlehe. “But his mother managed to get a visa by selling a painting and obtained the father’s release in this way.”

In his new home, Edward Engelberg became a professor of comparative literature at Brandeis University. He died in 2016. “I found an article about him that his son had written as a journalist,” says Schlehe. “I contacted the son and he was very supportive – answering questions, sending pictures, and telling personal anecdotes about his father.” This contact made the project special for Schlehe, as “it’s not every day that you get so close to the children’s fates.”

And then there was the moving video featuring ‘her’ schoolboy Edward Engelberg, where he was interviewed about the painting. “It was very emotional to see and hear him. He recalled various dramatic events from his childhood – such as the day after the Night of Broken Glass or how he ate a bar of chocolate with joy and relief after crossing the Swiss border with his family.”

They were normal children – children just like we used to be. The dreadful circumstances of their lives and the things they had to go through are harrowing.Derek Lesho

Schlehe’s fellow student Derek Lesho was able to find a lot of information while researching the fate of Paul Nußbaum, who was numbered 34 on the photo. Nußbaum also managed to flee to America. “He arrived in the United States in 1939 and made a career as an attorney in Baltimore,” says Lesho, who also came into contact with Nußbaum’s children while searching for traces of him online. “They were pleasantly surprised when somebody inquired about their father’s fate. We had a discussion via Zoom and they plan to visit Munich to learn more about the project.”

Paul Nußbaum and Edward Engelberg were among the lucky ones who managed to leave Germany before it was too late. The volume of source material out there was correspondingly large and was supplemented through the support of relatives. For example, Derek Lesho was able to view the diary Paul Nußbaum kept after his flight to the United States.

Aside from the entries detailing life in Munich, the family’s flight, and the experience of having to find one’s bearings in a foreign country, there was the poignant circumstance that he had been gifted the diary by a classmate who did not survive the Shoah: Berta Sandbank – known as “Bertel” – who was numbered 28 on the class photo. According to the testimony of her classmates, she was a very popular child, intelligent and sporty, jolly and healthy. When her family received the news of the death of her father in Dachau concentration camp – supposedly from a heart attack but actually he was beaten to death – her mother poisoned herself and her children out of desperation and hopelessness – Bertel and her brother survived.

On 10 April 1942, Bertel Sandbank was deported and murdered in the Izbica Ghetto, a transfer point for the Belzec and Sobibor extermination camps in Poland. “I found that utterly heartbreaking,” emphasizes Lesho. “They were normal children – children just like we used to be. The dreadful circumstances of their lives and the things they had to go through are harrowing.”

Derek Lesho investigated the fate of Paul Nussbaum. | © privat

Through their work, the students got to build a bridge across time, as it were, and connect the past to the present, something they very much appreciated.

“We were given a lot of freedom; we had to actively pursue our research and contact the descendants of the children. It wasn’t a run-of-the-mill project course; it was very moving,” praises Derek Lesho.

The classroom-based components were accompanied by events such as a guided tour of the Cultural Center of the Jewish Community of Munich and Upper Bavaria and of the Ohel Jakob Synagogue in Munich. Also, the students participated in a video conference with the Yad Vashem remembrance center in Jerusalem, where they learned all about the work of the memorial site.The essays that the students wrote about their research were prepared in the style of entries for the Biographical Memorial Book of the Jews in Munich.

The project was presented to the public on 16 May 2024, the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the Jewish Public Elementary School in Munich. There are plans to use the same format to investigate other photos or lists of names in the future, and a follow-up project course is slated for the coming winter semester. This will encompass an excursion to Kaunas in Lithuania – where most of the pupils of the Jewish Public Elementary School murdered by the Nazis met their end.